For centuries, the dominant Western image of God has been

one of omnipotence—a being who is all-powerful and who controls the

destiny of heaven and earth and all who dwell there. But that’s not the only

image of God. And it’s an image that says more about our culture than it does

about God.

Franciscan friar and social activist Richard Rohr has said: “Your image of God creates you.”

Thus, if we imagine God as all-powerful and all-controlling, we become a people

who hunger for power and control. If, however, we imagine God as one who

suffers with us, we become a people

who act out of compassion and mercy. Similarly, if we imagine God as that which

calls us to do good, then we become a people who listen for that “still

small voice.”

As process theologian Catherine Keller has pointed out, there is no Biblical

term for omnipotence. In fact, the closest thing to an expression of God as

omnipotent in the Bible is “the Almighty,” a rather inadequate translation of the

Hebrew term El Shaddai, which literally

means “the one with breasts.” It is a term that suggests a nurturing deity, one

that is the source of life. But it does not suggest omnipotence.

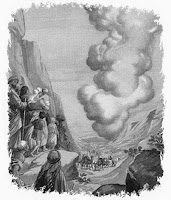

There are many images of God in the Bible: God the creator,

God the destroyer, God the pillar of cloud and

If it is true that our image of God creates us, then it

is up to us to choose. In some ways, no image of God at all (essentially an

atheistic understanding of ultimacy) is the truest image as it acknowledges our

ultimate unknowing and leaves it up to us to do something with this perceived

void.

However, whatever image of God we choose (even no image

at all) has a profound effect on who we are and how we act.

If we are to be agents of transformation in the world,

our image of the ultimate must be open-ended, forever becoming something other

than what it is or has been, something that is more of an invitation than it is

a declaration. Something more like the pillar of cloud and fire than the

embittered dispenser of merciless judgment.

For far too long, we have cowered behind images of God as

omnipotence, images that have been contrived and controlled by those in power—the empire-builders,

the colonizers, the conquerors—in order to retain and exert and expand their

dominance over others.

Religious transformation requires us to shed the oppressive

garment of omnipotence and instead put on what the apostle Paul called “an

armor of light”—a newfound layer of awareness and illumination that enables us

to see things both as what they are and as what they might become.